I did an interview on the 2021 German Federal Election with 95bFM „The Wire with Justin“. You can listen to it here.

New Book Review in Politische Vierteljahresschrift

I have written a book review of „Johnson, Dennis W. (2020): Campaigns and Elections. What Everyone Needs to Know New York: Oxford University Press“ for Politische Vierteljahresschrift, Vol. 26, Issue 4 (2021). It’s open access and you can read it here.

Talk about Social Media in the 2020 NZ Election at University of Canterbury

If you are in Christchurch March, 9th 2021, join me for a talk about our New Zealand Social Media Study (NZSMS) in the 2020 New Zealand General Election at the Media & Communication (COMS) Research Seminar. For details see below.

New Editorial Team Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties (JEPOP)

I am excited to announce that I, along with a fantastic team of three Co-Editors, Christopher J. Williams (University of Arkansas at Little Rock), Robin Best (Binghamton University), and Zachary Greene (University of Strathclyde Glasgow), as well as two deputy editors, Ko Maeda (University of North Texas) and Matthew Singer (University of Connecticut), will be taking over the editorship of the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties this summer. We look forward to your submissions!

Spotlight lecture – The Battle over America

If you are in Wellington, register for our „Spotlight lecture: The Battle over America“, Friday 6 Nov, 12.30–1.30pm, Rutherford House Lecture Theatre 1 (RHLT1), Pipitea campus, Bunny Street. I will try to make sense of the likely post-election power struggle in the USA.

Update: A recording of the lecture is meanwhile available on You Tube

New Radio interview with RNZ morning report: Study finds how politicians used social media during election

This week I spoke with Radio New Zealand’s Morning Report again about who the most active campaigner on Facebook during the 2020 New Zealand election was and what communication strategies and styles the party leaders followed in their social media campaigns.

Listen to the full interview here.

New Blogpost: #nzvotes: The dynamics of campaign communication on Facebook

Repost from Te Herenga Waka Victoria University’s Website

During the 2020 general election campaign, the New Zealand Social Media Study (NZSMS) has now harvested more than 3,000 Facebook posts from the Labour Party, National Party, New Zealand First, the Green Party, ACT, the Māori Party, The Opportunities Party (TOP), Advance New Zealand (which also includes the New Zealand Public Party), the New Conservatives, and their leaders.

The data at this point presents a revealing picture of the use of Facebook in the campaign. The project’s findings have been widely reported and some of the political parties have responded to the team’s research. In line with the project’s findings that Advance New Zealand was spreading misinformation around COVID-19, Facebook, having conducted its own investigation, took the unusual step of ‘deplatforming’ the party just two days before the election. In justification, a spokesperson for Facebook said it “does not allow anyone to share misinformation about COVID-19 that could lead to imminent physical harm”. Something the NZSMS team had warned about early in the campaign.

In this final post, NZSMS research leaders Professor Jack Vowles and Dr Mona Krewel from Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington’s Political Science and International Relations programme analyse the information collected throughout the last four weeks of the campaign and show how the parties’ social media unfolded.

Did social media campaigns become more positive or more negative over time? Was the spread of false information a single event for parties or did they continuously post fake news and half-truths? What political topics were trending over the course of the campaign?

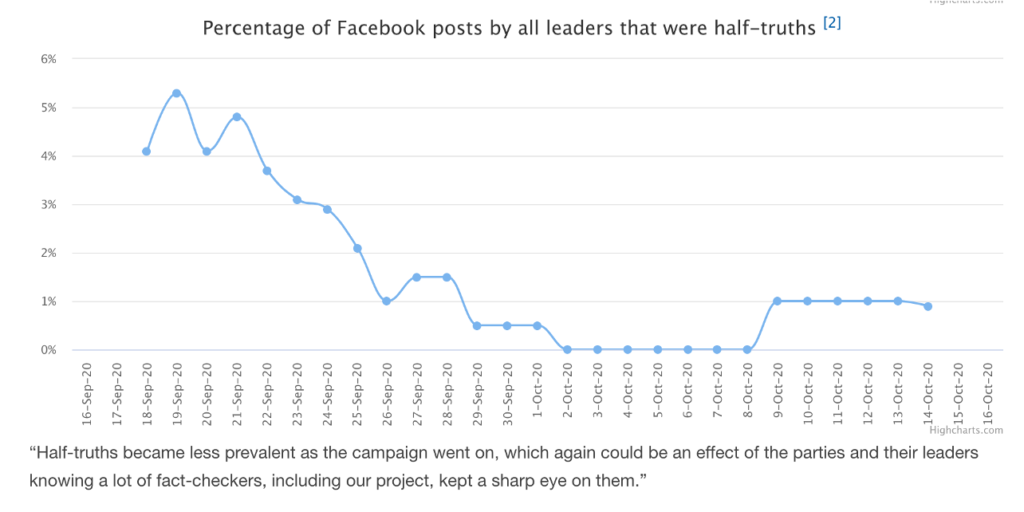

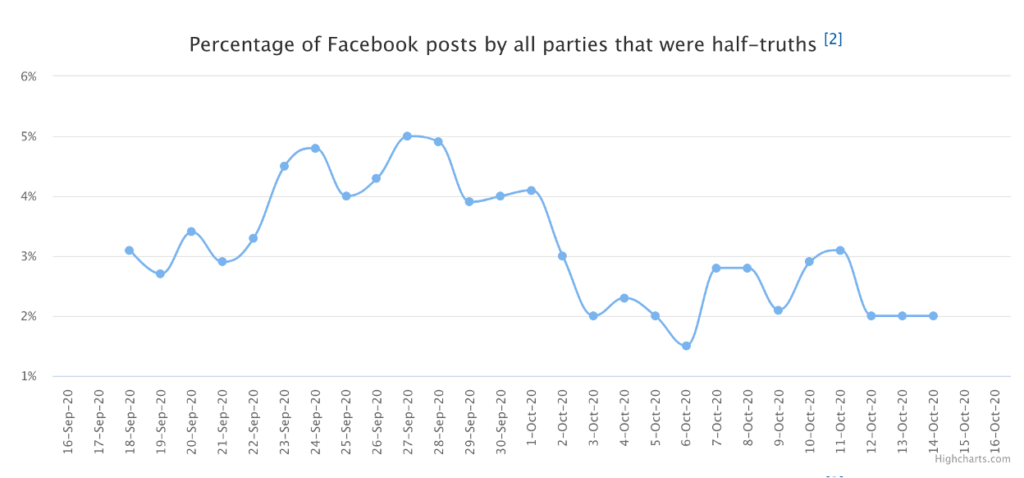

As noted, Professor Vowles’ and Dr Krewel’s research has been widely reported and observed by the political parties, which raises the intriguing prospect that the reports of their research could have affected some parties’ subsequent posting strategies. Those using negative strategies could have become less negative, those promoting fake news and half-truths could have become less prone to do so. On the other hand, changes in strategy over the campaign could also simply reflect internally driven choices.

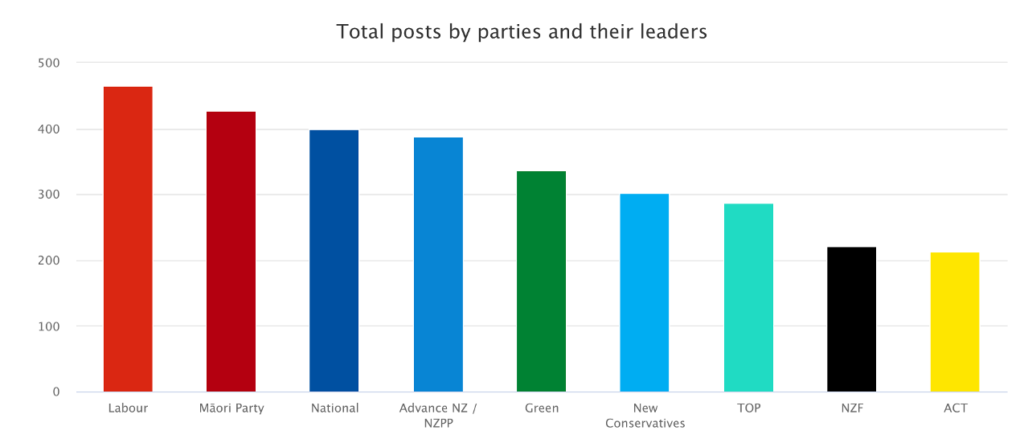

Who has been the most active campaigner on Facebook in the 2020 election?

“We have added together all activity by the political parties and their leaders. The biggest users of Facebook were, as expected, the Labour Party and New Zealand’s social media powerhouse Jacinda Ardern,” says Dr Krewel.

“The party coming in second is a bit of a surprise: the Māori Party. The main source of this is a large number of posts from party co-leader John Tamihere, who, of all the leaders, posted the most. Next comes National, as expected, but followed very closely by Advance New Zealand, whose leader data came only from Billy Te Kahika; whereas co-leader Jamie-Lee Ross did not use Facebook during the campaign. With two co-leaders active for the Green Party, they come next in the ranking order, followed by the New Conservatives and TOP. The two least active parties on Facebook were New Zealand First and ACT.

“The major parties, of course, have the deepest pockets and can invest a lot in their social media communication to woo voters online. However, the example of the Māori Party shows social media is also a great opportunity for the minor parties to make up for a smaller budget when they have a very engaged user of social media in their ranks.”

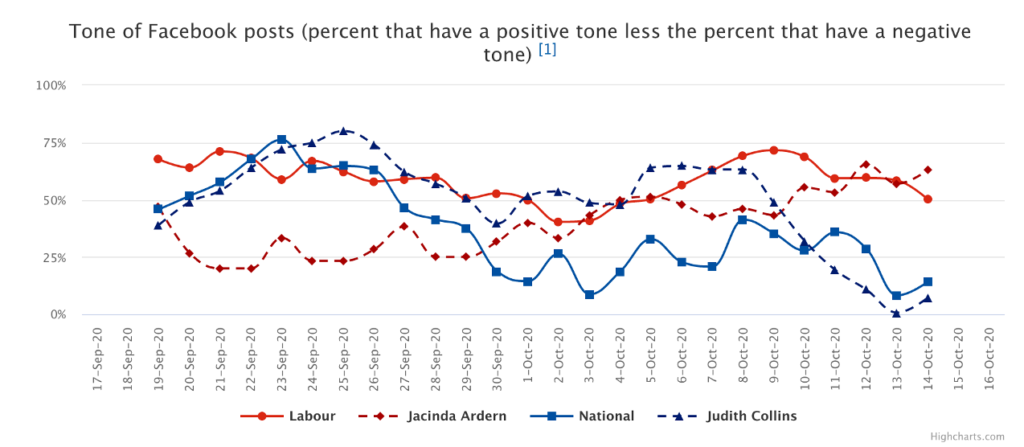

And what about the overall tone of the campaign?

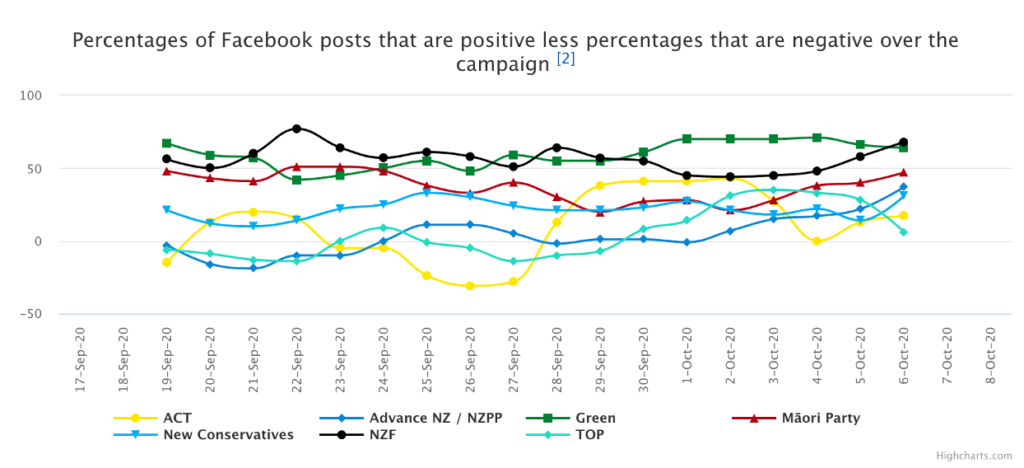

“In early posts, we already explained the reasons why some parties ‘go negative’ and others ‘go positive’,” says Professor Vowles. “Government parties are more likely to choose a positive tone in their campaign, opposition parties have good reasons to be negative and attack, as they need the media attention.

“It is therefore surprising that, until the very end of the campaign, Jacinda Ardern’s ratio of positive to negative posts was lower than that of National leader Judith Collins. However, this is largely explained by Jacinda Ardern’s high rate of neutrality of tone early in the campaign. She started into the campaign by mostly campaigning in a ‘Prime Ministerial incumbent mode’. But roughly a week before the election, she finally geared up into campaigning mode, as was apparent in the final leadership debate. Jacinda Ardern’s positivity ratio is consistently tracking upward until it exceeds that of Judith Collins. Meanwhile, Judith Collins’s posts go so negative in the last week that, at one point, her positive and negative statements go into balance.”

“Focusing on the parties, meanwhile, Labour’s posts remain strongly positive throughout the campaign, while National’s ratio starts positive but becomes less so as the campaign progresses, following Judith Collins into almost negative territory by the last few days. Informed by repeated polling showing they were making no ground, the National Party and its leader were becoming increasingly desperate and tried to attack wherever they saw a chance.”

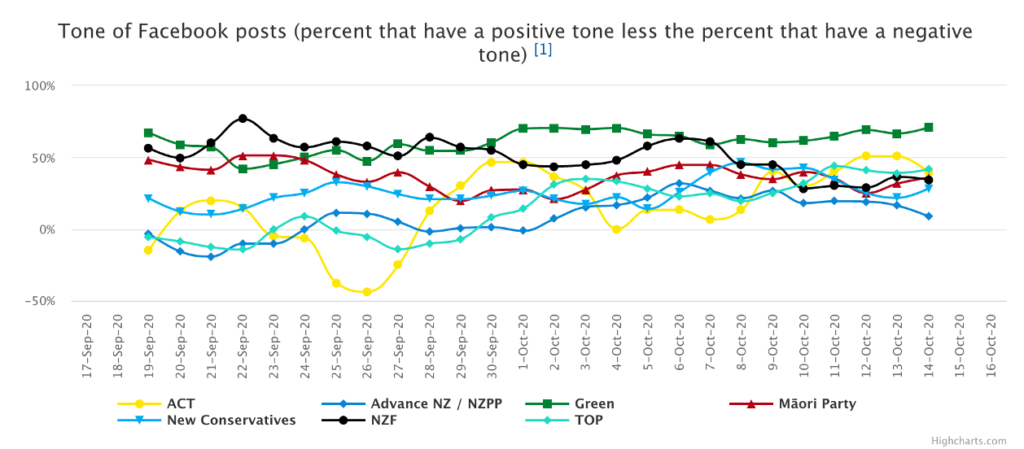

“The Green Party stayed in positive territory throughout,” says Professor Vowles. “The Māori Party is consistently positive at a slightly lower level, trending down only slightly as the campaign goes on. The New Conservatives are less positive, again, although becoming slightly more positive over the campaign. This could either have strategic reasons, as they wanted to ensure voters make their tick for them and not only vote against their political opponents, or be a reaction to being publicly called out for negativity. We cannot know for sure.”

Two parties started negative but became more positive as the campaign went on: ACT and TOP.

“ACT’s tone shows most variation, indicating either close attention to campaign impact over the campaign or, alternatively, perhaps a more random or uncoordinated line of attack,” says Professor Vowles. “In late September, ACT’s posts were 40 percent more negative than positive, but bounced back to 40 percent more positive only a few days later.”

“The trend for New Zealand First starts positive, as one would expect from a Government party,” says Dr Krewel, “but trends downward. Over the last week, New Zealand First ends up with much the same ‘tone ratio’ as that of ACT: at about 30–40 percent positive compared with 70 percent positive for the Green Party and between 50 and 60 percent for Labour.

“New Zealand First’s declining positivity was apparent more generally. Commentators have already identified this behaviour as a possible reason for New Zealand First’s failure to make more than marginal headway as the campaign went on. As a Government party, they should have concentrated more on their achievements in office.”

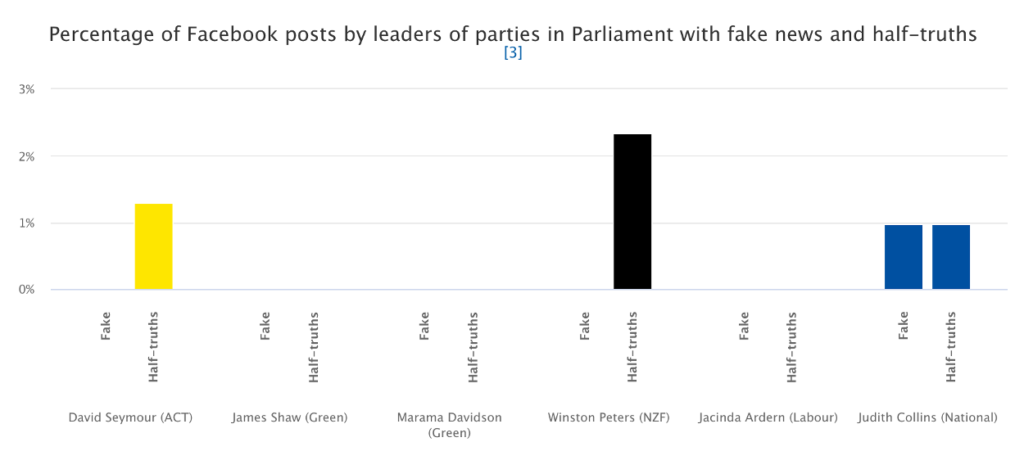

But what about the strongest form of dirty campaigning: misinformation?

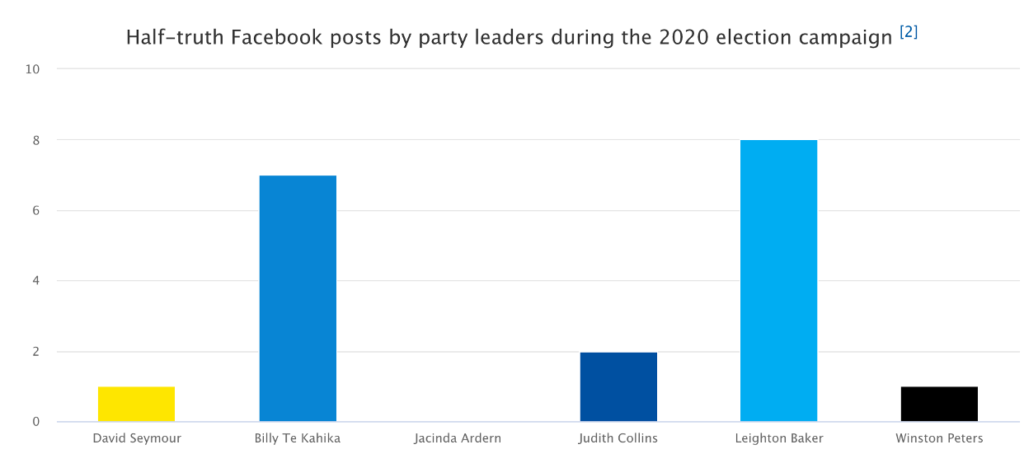

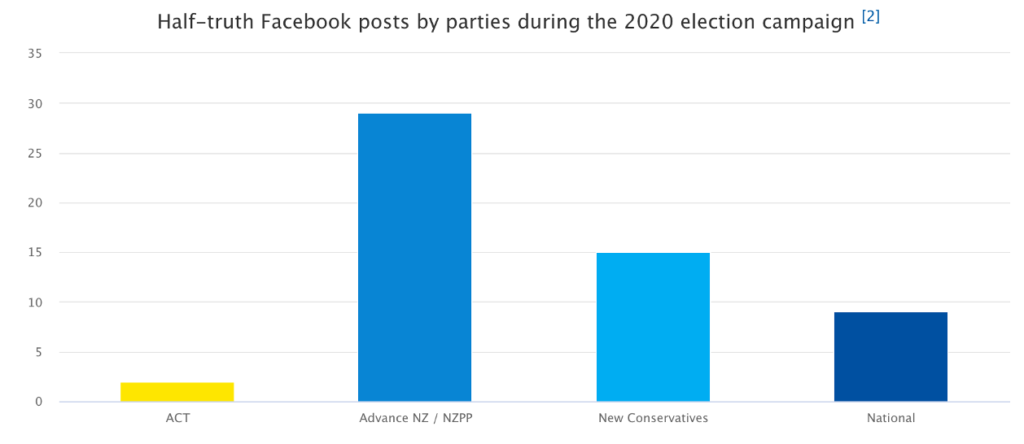

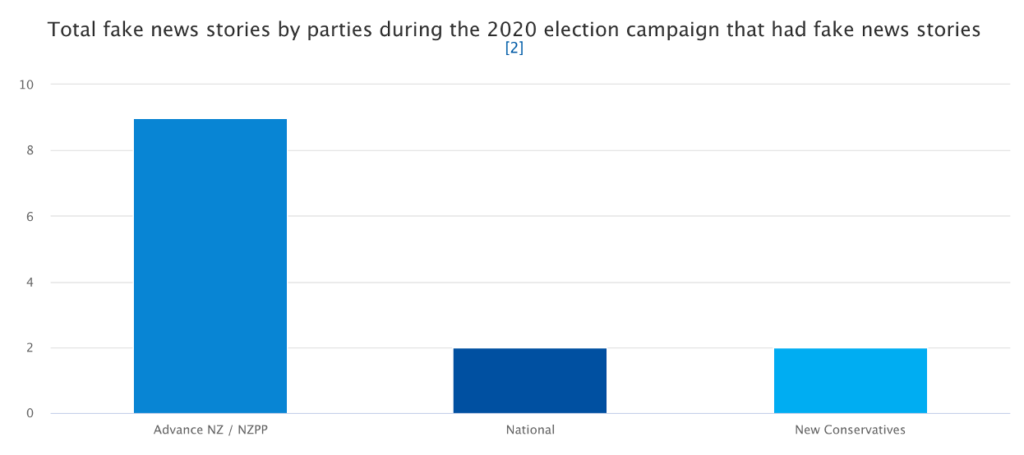

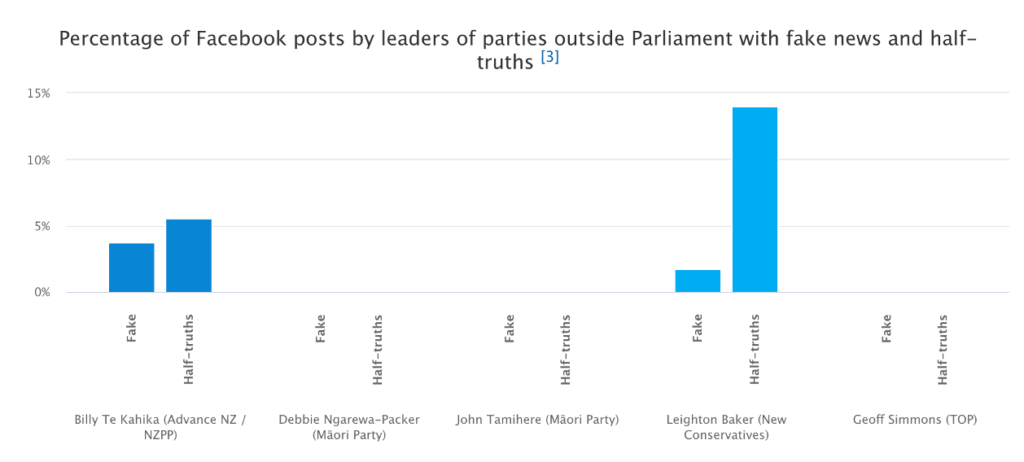

“Compared with the total number of posts under scrutiny (more than 3,000), half-truths (fewer than 75 posts) and ‘fake news’ (less than 20 posts) were relatively absent in the 2020 New Zealand election and were mostly concentrated in the Facebook pages of Advance New Zealand, the New Conservatives and their respective leaderships,” says Professor Vowles.

“Jacinda Ardern expressed no half-truth and Judith Collins two. As a party, Labour also did not post any half-truths, but the National Party was responsible for nine. ACT leader David Seymour posted one half-truth, his party two. New Zealand First leader Winston Peters posted also only one half-truth, his party none. The Green Party like Labour had none.

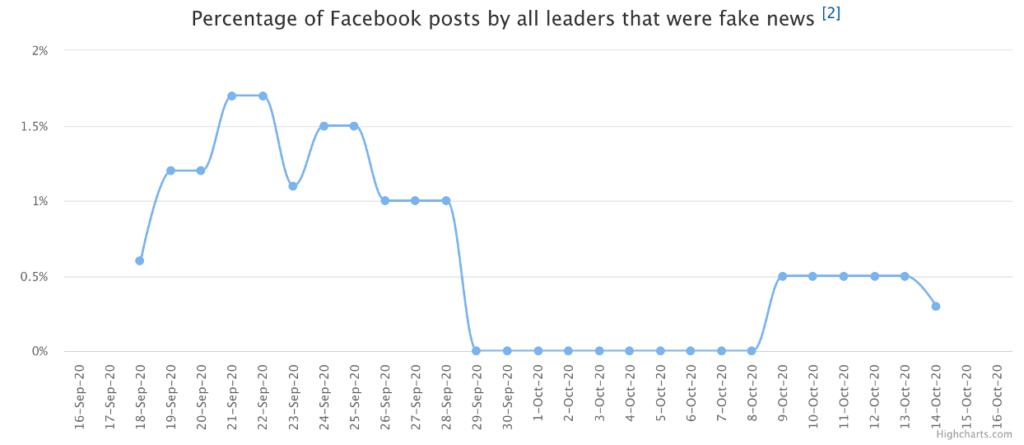

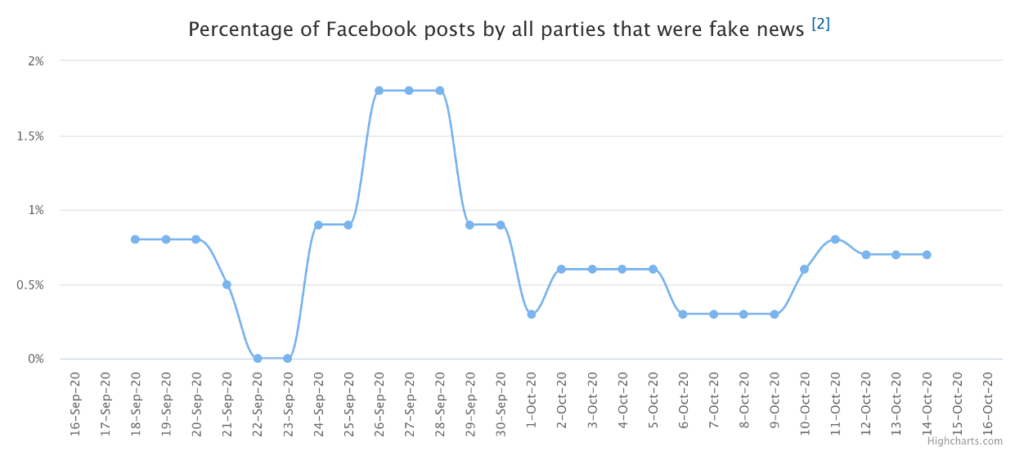

“Half-truths became less prevalent as the campaign went on, which again could be an effect of the parties and their leaders knowing a lot of fact-checkers, including our project, kept a sharp eye on them.”

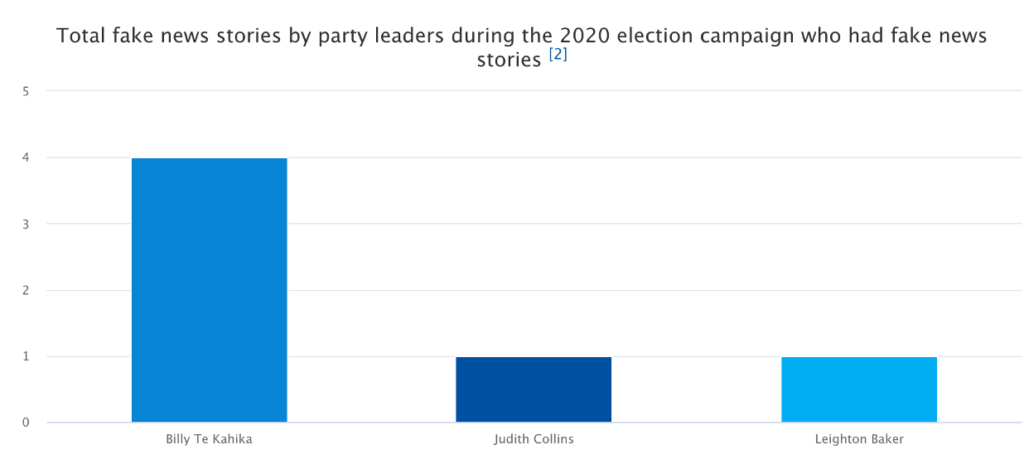

Fake news was only found in the posts of Advance New Zealand (9), Billy Te Kahika (4), the New Conservatives (2), their leader, Leighton Baker (1), Judith Collins (1), and the National Party (2), says Professor Vowles. “Fake news posts also fell as the campaign went on, with a slight recovery in the last week, primarily from Billy Te Kahika.”

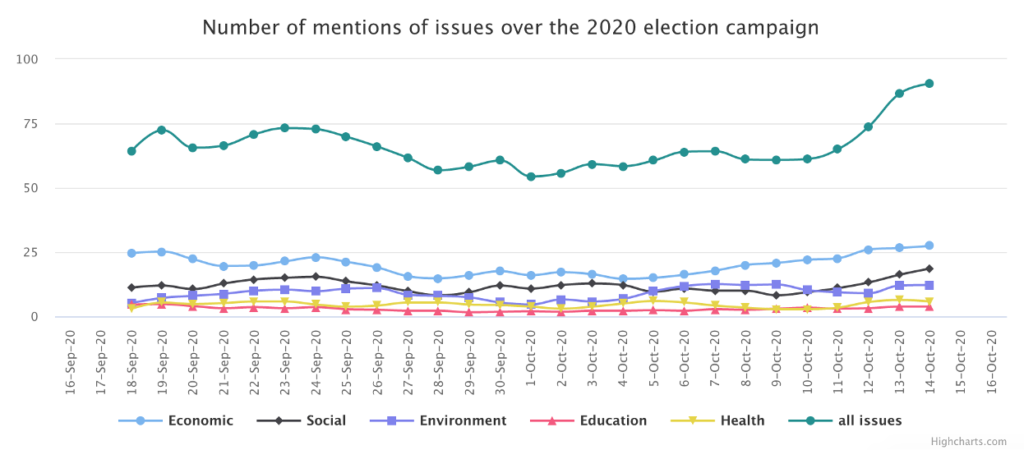

What political topics were trending over the course of the campaign?

“Of the slightly over 3,000 Facebook posts coded, more than 2,500 contained policy or issue content,” says Dr Krewel. “That is a lot. It means today’s campaigns are wrongly accused of being unpolitical. Modern campaign tools such as social media are not necessarily superficial and about only personalities rather than issues. However, that there is a certain number of non-political posts also shows social media is a medium that requires political leaders to be more informal and personal. But most posts are still political.

“As reported in earlier posts, the economy remained the major issue, the number of mentions dropping somewhat mid-campaign. Social and labour market issues were the second-most-mentioned issue, remaining consistent over most of the campaign, rising slightly at the end. Environmental and energy issues came next, followed by health (not including COVID-19) and transport, but none of these showed much variation over the campaign.”

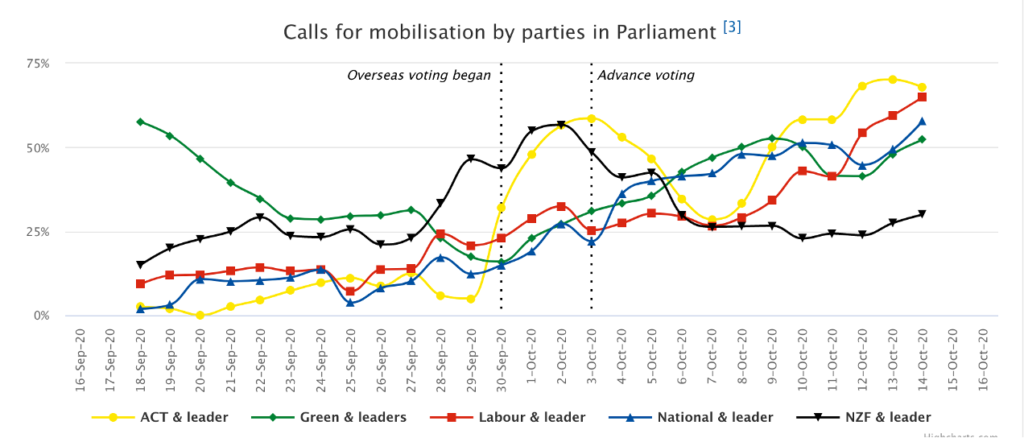

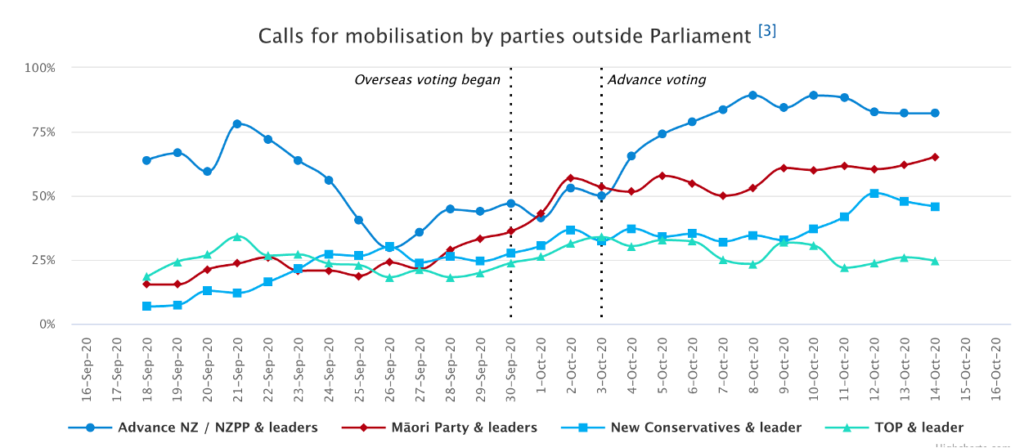

And finally, did the campaigns do a good job in mobilising voters to turn out?

According to Professor Vowles, the pattern of voting returns has changed significantly over the past two or three New Zealand general elections.

“Advance voting has been increasingly facilitated and encouraged, changing the incentives shaping parties’ mobilisation efforts over the campaign. No longer is there a concentration on ‘getting out the vote’ on election day. Efforts are spread over the period of advance voting.

“However, not all parties’ Facebook posts designed to encourage going out to vote fit this pattern. Labour, National and the Māori Party show the clearest ‘step-up’ behaviour, although National’s efforts stepped up earlier and Labour only reached its peak in the final week. ACT stepped up its mobilisation efforts at the beginning of the advanced voting period but then fell back, subsequently redoubling its efforts over the last two weeks.

“The Green Party also stepped up when advanced voting started and steadily intensified its efforts until election day, although had also put in a very strong effort at the very beginning of the campaign, as did Advance New Zealand. Indeed, Advance New Zealand appears to have put almost all its efforts into mobilisation after the advent of advanced voting.”

But, says Dr Krewel, “it is New Zealand First that stands out in its apparent failure to transmit mobilisation messages during the period likely to have been most effective. New Zealand First seems to have intensified its efforts in the lead-up to advance voting but then failed to maintain the momentum, putting in the least effort of all the parties even just before election day. But as New Zealand First was a relatively low user of Facebook, this failure to concentrate its mobilisation efforts on the platform effectively may have mattered little in the end.”

CrowdTangle, a public insights tool owned and operated by Facebook, has been used to collect the data on which this commentary is based. This sample has then been coded by five human coders on the basis of CamforS/DigiWorld’s codebook.

1. A post could include both negative and positive statements. Based on the valence and strength of the used statements, pictures or emotions, the post could be of a negative or positive but also balanced nature. This tendency could be derived from the overall impression of the statements, pictures and emotions included in the post. The decisive factor for coding was the impression about the valence of the statements, pictures and emotions an average reader would get after looking at the post.

A post contained negative campaigning when it aimed at critically presenting the political opponent. This involved all forms of attack on the political opponent (party, politician, coalition, institution). Negative campaigning criticises socially relevant topics, uses stereotypical traits, highlights shortcomings as well as criticises and attacks qualities and behaviour of parties, politicians and related issues. Moreover, exaggerations and negative emotions such as fear, envy, blame and anger have also been considered negative campaigning.

A post contained positive campaigning when it included positive statements, pictures and emotions of a supporting, encouraging, affirmative, beneficial or assertive nature and presented the advantages of a party’s own candidate, their goals and competencies.

The graph shows the positive less the negative news. A five-day moving average has been used to smooth out short-term fluctuations and highlight the trend of the campaign period.

2. A post contained fake news when it was completely or for the most part made up and intentionally and verifiably false to mislead voters. The usual disagreements and accusations between political actors were not coded as fake news here. If a coder assumed a post could include fake news, but was not fully sure, they were asked to do some fact-checking and visit news websites of reliable sources to see if something had already been identified as fake news. In case of doubt, coders were asked to take a conservative approach and code the absence of fake news. Therefore, the graphs presented here under- rather than overestimate the extent of fake news in the campaigns.

When a post did not classify as fake news, coders were additionally asked if it contained half-truths—eg. things that were not completely accurate. Something coded as fake news automatically was coded as half-truths too. However, not all half-truths also qualified as fake news.

3. A post contained a call for mobilisation when it encouraged the user to actively engage with and support the party in different ways and ultimately aimed at initiating/generating political participation. We distinguished between calls for mobilisation online and offline. Mobilisation online included all actions that take place online, like sharing a post or participating in an online petition. Mobilisation offline included all actions that take place offline, like going to cast a ballot or knock on doors.

A five-day moving average has been used to smooth out short-term fluctuations and highlight the trend of the campaign period.

Should we fear fake news in our politics?

This Sunday (Oct 25) a longer interview with me on the results of the New Zealand Social Media Study (NZSMS) was aired as part of RNZ’s Mediawatch. Listen to the entire feature on fake news and social media here.

TV Interview with TVNZ breakfast on Social Media and NZ Political Parties

On the day before the NZ election I have spoken with TVNZ breakfast about the newest findings in our Social Media Study regarding negative campaigning, fake news, and half-truths among the minor parties. And the question: is Advanced New Zealand really populist?

Watch the full interview here.

New blog post: Negative campaigning, fake news, and half-truths among the minor parties. And the question: is Advance New Zealand really ‘populist’?

Repost from Te Herenga Waka Victoria University’s Website

The leaders of the smaller parties in the 2020 New Zealand general election faced off in last week’s minor parties’ debate on TV. But how well are the campaigns of the minor parties and their leaders going on social media? What political topics are they campaigning on? Are they and their leaders ‘going dirty’? And is yesterday’s shutdown of Advance New Zealand’s Facebook page justified?

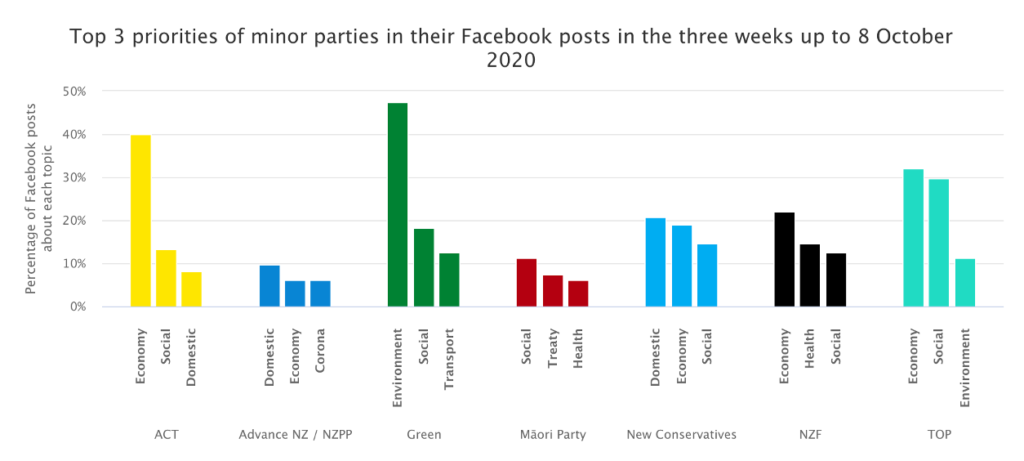

In their content analysis study of social media, Professor Jack Vowles and Dr Mona Krewel from Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington’s Political Science and International Relations programme have now coded and analysed 1,936 Facebook posts placed by political parties and their leaders for the time period of 17 September–8 October, and will continue to code new posts until election day. The parties covered are Labour, National, the Greens, New Zealand First, ACT, The Opportunities Party (TOP), the Māori Party, the New Conservatives, and Advance New Zealand, as well as their leaders.

This week, they shine light on the Facebook campaigns of the minor parties and their leaders, including some of those left out of the multi-leader debate.

“The major parties are focusing their campaigns on the economy, because more voters tend to identify the economy as important,” says Professor Vowles. “Among the minor parties, some identify other issues. ACT, New Zealand First, and TOP focus their campaigns on the economy; Advance New Zealand, the Greens, the Māori Party, and the New Conservatives emphasise other issues.”

The Green Party focuses on the environment, he says, “which is not surprising, given their ‘reason for being’, and voters who identify the environment as their highest priority also tend to see the Greens as the party most committed to dealing with environmental issues. They are simply emphasising their main strength in their social media communication.

“The issues the Māori Party chooses to highlight are also consistent with what they stand for: they campaign on social issues in order to achieve better outcomes for Māori, who tend to be more concentrated among those on lower incomes. And, of course, the Māori Party also has the strongest focus on the Treaty of Waitangi.”

The story is a little different for Advance New Zealand, which also includes the New Zealand Public Party, says Dr Krewel. “Their agenda consists of seeking to convince voters the Government’s lockdown policies have unnecessarily limited New Zealanders’ freedom. Besides that, they have declared themselves an anti-corruption party—despite one of their leaders being investigated for corruption himself. This adds up to a strong focus on what we classify as domestic policies. The coronavirus also looms large in Advance New Zealand’s social media communications, as they are attempting to exploit the pandemic by spreading coronavirus conspiracy fears. Campaigning on economic insecurity and health is intended to attract people into their extreme ideology who under different circumstances would not have identified themselves with such polices. They hope spreading COVID-19 conspiracy theories and misinformation will be an effective strategy for them to radicalise anxious voters.”

However, adds Dr Krewel: “Opinion polling indicates only a few people are likely to vote for them, so their efforts have not been very effective, despite their social media impact. And on social media they have now also taken it too far by posting anti-vaccination adverts that yesterday led to Facebook’s decision to take their page down. However, they will surely use this as an opportunity to make a point against the global elites and the media trying to silence them, claiming to be the last party that is telling people the truth.”

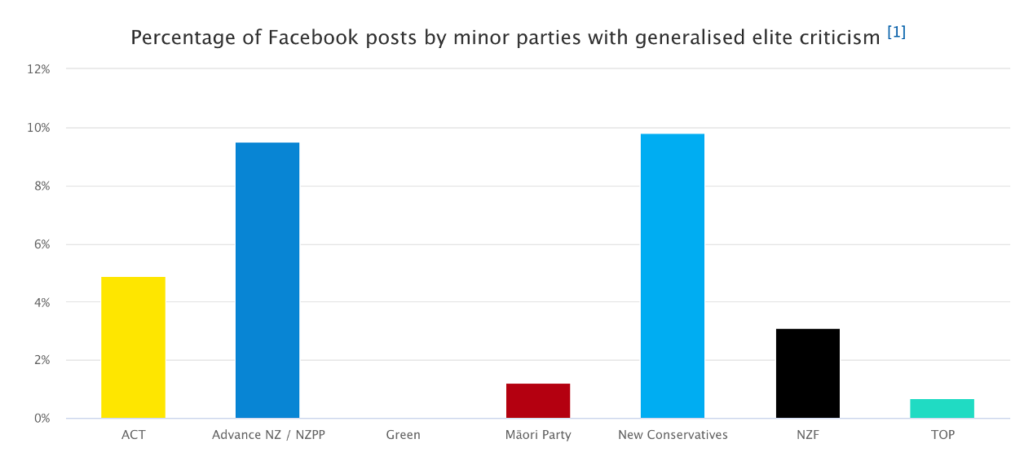

Professor Vowles notes that some commentators and political scientists describe such tactics and appeals as ‘populist’. “The New Zealand Public Party in particular campaigns against a global elite they claim has hidden objectives that lie behind governments’ responses to the coronavirus. The New Zealand Government and mainstream politicians are accused of being in thrall to global interests. This is an approach like that of the European radical right parties that border on fascism and are often described as ‘populist’. Indeed, nearly 10 per cent of Advance New Zealand—and also the New Conservatives—used a communication strategy of generalised elite criticism that is often labelled as populist. Such criticism is an obvious strategy for parties that have never been in power and therefore can campaign against the ‘establishment’ in general.”

But Professor Vowles adds that “while Advance New Zealand occasionally uses populist language centred on ‘the people’, by far its strongest language lies in the protection of individual freedom, not usually the territory occupied by a populist party. Like New Zealand First, its appeal is also nationalist, seeking to defend national sovereignty, and it has a strong Māori dimension.

“If we think of populism in two senses—as a campaign strategy based on the use of language and as a set of democratic norms—then Advance New Zealand uses some populist language, but also other language not usually defined in those terms. And in its claims to promote and defend the populist democratic norm that governments should be representative of ‘the people’, and thus majority public opinion, Advance New Zealand is no different from almost all New Zealand’s other political parties.

“In its opposition to the current coronavirus policy settings, Advance New Zealand rejects majority public opinion in favour of a defence of individual freedoms, fatally undermining its populist democratic credentials. Most New Zealanders continue to support a policy of collective action to protect society from the coronavirus, a preference far more consistent with the norms of democratic populism. If Advance New Zealand were a true populist party, we might expect them to be attracting more votes.”

For most of the campaign, like the major parties, the minor parties have been communicating with much more positive than negative language and their campaigns have become more positive over the course of the campaign, says Dr Krewel. “It is not surprising they become more positive as the campaign goes on. The closer we get to election day, the more the parties need to bring the focus of their campaigns back to themselves. You can attack your political opponents during the campaign, but on the ballot paper voters need to vote for you, not against the target of your negative messaging. Especially in a multi-party system where voters have a lot of options, you need to ensure they not only know for whom not to vote but also where to make their tick.”

Dr Krewel notes that of the small parties in Parliament ACT has gone through much more of a roller-coaster of positive and negative campaigning over the course of the campaign than other parties. “This does not speak for a very coherent campaign strategy,” she says. “Or as campaigners say: you have to stay ‘on message’ in a campaign. You have to stick to the prearranged script or ideas you want to communicate and repeat those messages persistently: for example, the decision to run an attack campaign rather than emphasising your own advantages. But ACT has changed its messaging erratically from positive to negative campaigning back and forth over the entire campaign.”

David Seymour might have won the multi-leader debate according to Vote Compass respondents, she says, “but his party most likely has not won the Facebook campaign battle. Their unsteady campaign communication has probably confused voters more than it has benefited ACT.”

As mentioned in last week’s post , the minor parties engage more in the spreading of misinformation than the major parties, says Professor Vowles. “But it seems the minor party leaders have mostly avoided being associated with the dissemination of fake news or lending their faces to posts that contain half-truths. They post much less fake news and half-truths than their parties. To give some examples, only 3.7 per cent of Billy Te Kahika’s posts have contained fake news and 5.6 per cent half-truths, while already in week two of our study Advance New Zealand/NZPP’s posts contained 6 percent fake news and 31 percent half-truths. It is therefore not surprising Facebook yesterday took the party’s page down, but so far has not yet taken any action against Billy Te Kahika’s page. Similarly, only 1.3 percent of David Seymour’s posts contain half-truths, while 9 percent of his party’s posts contained information that was not fully accurate. There is an overlap in who posts misinformation. It is the same ‘usual suspects’. Where the parties engage in spreading false information, the leaders do too. It is simply not as much.”

For Dr Krewel, this bears some resemblance to the findings of research on negative campaigning in television advertisements in the United States: “Some of the most negative TV advertisements in the US tend to come from third-party actors, such as the so-called PACs (political action committees). These are organisations that pool campaign contributions and fund campaigns. The candidates they support leave it up to the PACs to attack their opponents to minimise a possible backlash and keep their own record clean. It seems that in a similar way the party leaders tend not to spread fake news or promote half-truths and try to keep a clean slate, letting their parties take the blame instead.”

CrowdTangle, a public insights tool owned and operated by Facebook, has been used to collect the data on which this commentary is based. This sample has then been coded by five human coders on the basis of CamforS/DigiWorld’s codebook.

Footnotes

- (1) A post contained populist elite criticism when it a) blamed the elite (from any sector) as a group/the system in general for problems and grievances the people suffer or when elites are held responsible for anything undesirable from the people’s perspective; when it b) questioned the elite’s legitimacy to take decisions; when it c) called for resistance against the elite and their ideas and for direct popular decisions; and when it d) accused the elite of betraying the people or acting against the people’s interest or being corrupt.

- (2) A post could include both negative and positive statements. Based on the valence and strength of the used statements, pictures or emotions, the post could be of a negative or positive but also balanced nature. This tendency could be derived from the overall impression of the statements, pictures and emotions included in the post. The decisive factor for coding was the impression about the valence of the statements, pictures and emotions an average reader would get after looking at the post.

- (2) A post contained negative campaigning when it aimed at critically presenting the political opponent. This involved all forms of attack on the political opponent (party, politician, coalition, institution). Negative campaigning criticises socially relevant topics, uses stereotypical traits, highlights shortcomings as well as criticises and attacks qualities and behaviour of parties, politicians and related issues. Moreover, exaggerations and negative emotions such as fear, envy, blame and anger have also been considered negative campaigning.

- (2) A post contained positive campaigning when it included positive statements, pictures and emotions of a supporting, encouraging, affirmative, beneficial or assertive nature and presented the advantages of a party’s own candidate, their goals and competencies. The graph shows the positive less the negative news.

- (2) A five-day moving average has been used to smooth out short-term fluctuations and highlight the trend of the campaign period.

- (3) A post contained fake news when it was completely or for the most part made up and intentionally and verifiably false to mislead voters. The usual disagreements and accusations between political actors were not coded as fake news here. If a coder assumed a post could include fake news, but was not fully sure, they were asked to do some fact-checking and visit news websites of reliable sources to see if something had already been identified as fake news. In case of doubt, coders were asked to take a conservative approach and code the absence of fake news. Therefore, the graphs presented here under- rather than overestimate the extent of fake news in the campaigns.

- (3) When a post did not classify as fake news, coders were additionally asked if it contained half-truths—eg. things that were not completely accurate.