The NZ Herald covers our social media study. Read the full article here.

Autor: Mona Krewel

Interview with RNZ morning report on the findings of the New Zealand Social Media Study (NZSMS)

Today I did an interview with Radio New Zealand’s morning report on the findings of our study on the Facebook campaigns of the parties and the candidates in the 2020 election and talked about fake news, half truths, and negative campaigning. You can listen to the full interview here.

Advance NZ worst offender of fake news on Facebook among parties – election study

TVNZ covers our study on the Facebook campaigs of New Zealand’s parties and their leaders as well and reports about our latest results on the use of negative campaigning and fake news. Read the full article here.

NZ Election 2020: Which parties‘ Facebook feeds are full of fake news and half-truths revealed in study

In a recent story Newshub confronts the parties with our results on the use of negative campaigning and fake news from our ongoing study about the Facebook campaigns of the parties and the candidates in the ongoing New Zealand election. Read the full article here

Study reveals which parties post the most fake news

This Friday, October 9, I joined the Radio New Zealand Panel to discuss some new results from our ongoing New Zealand Social Media Study (NZSMS) on the use of negative campaigning and fake news in the 2020 New Zealand election. Listen to the full interview here.

New blog post: “New Zealanders deserve a positive election,” said PM Jacinda Ardern. But are they getting it?

Repost from Te Herenga Waka Victoria University’s Website

During an election campaign, one observes frequent insults, mudslinging and distortion. From the standpoint of political campaigners, the beauty of negative campaigning consists of its ability to affect everyone. Even convinced supporters of a party under attack strongly remember negative information about their party. Campaigns in the United States have a reputation for making frequent use of dirty campaign techniques. The 2016 presidential election is one of the best-known examples of negative campaigning and the spread of fake news on social media. But how nasty are New Zealand’s social media campaigns when compared with others? Do we have to be seriously concerned?

There

are some grounds for disquiet. During the 2017 general election

campaign, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) received only 16

complaints about advertising with false content. With 10 days to go

before the 2020 election, it had received 80, with more likely to come.

Most of these complaints have been about newspaper advertising, which is

not usually repeated after a ruling. But compliance to ASA rulings is

voluntary, and the advertisements are continuing online.

In

their content analysis study of social media, Professor Jack Vowles and

Dr Mona Krewel from Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington’s

Political Science and International Relations programme have coded and

analysed 1,181 Facebook posts placed by political parties and their

leaders for 17 September–1 October, and will continue to do so over the

coming weeks until election day on 17 October. The parties covered are

Labour, National, the Greens, New Zealand First, ACT, The Opportunities

Party, the Māori Party, the New Conservatives, and Advance New Zealand,

as well as their leaders. Their data confirms the extent of ‘fake news’

so far distributed but puts it into a wider perspective.

Based on this data, Professor Vowles and Dr Krewel look at mobilising versus demobilising campaign techniques and the incidence of fake news and ‘half-truths’. “Negative techniques are very important,” says Dr Krewel, “as negative posts psychologically stick with our brains. And once negative information is planted, it is hard to forget. It is more ‘sticky’ than positive information and we unfortunately remember it much better than positive information and give it more weight.”

Professor Vowles points out most people share a common normative ideal about election campaigns: a campaign should activate and mobilise voters to cast their votes. “Studies have shown that as long as the volume of negative and positive political communication in a political campaign is about the same, campaigns can increase turnout. But as the volume of negative political advertising increases, turnout tends to be adversely affected. Fair election campaigns in which the competing parties engage in constructive criticism instead of mudslinging can motivate people to vote. Otherwise, they can alienate citizens from politics.”

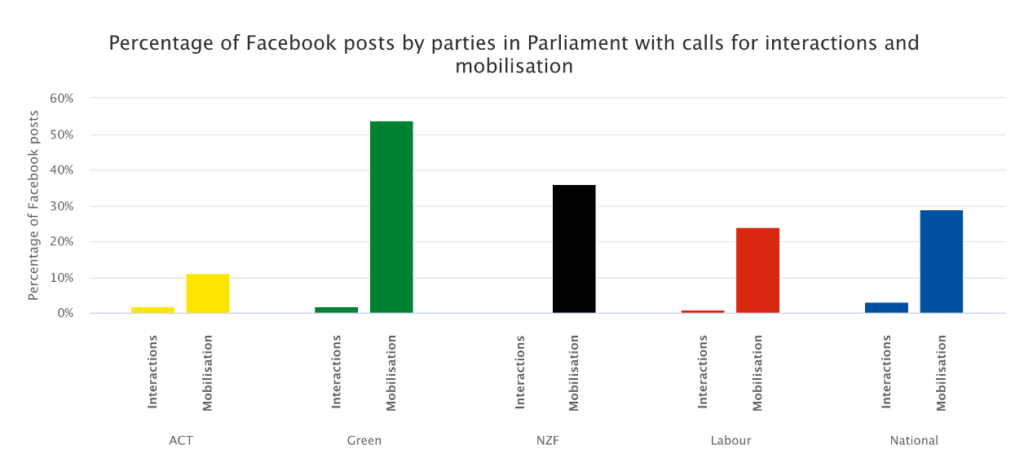

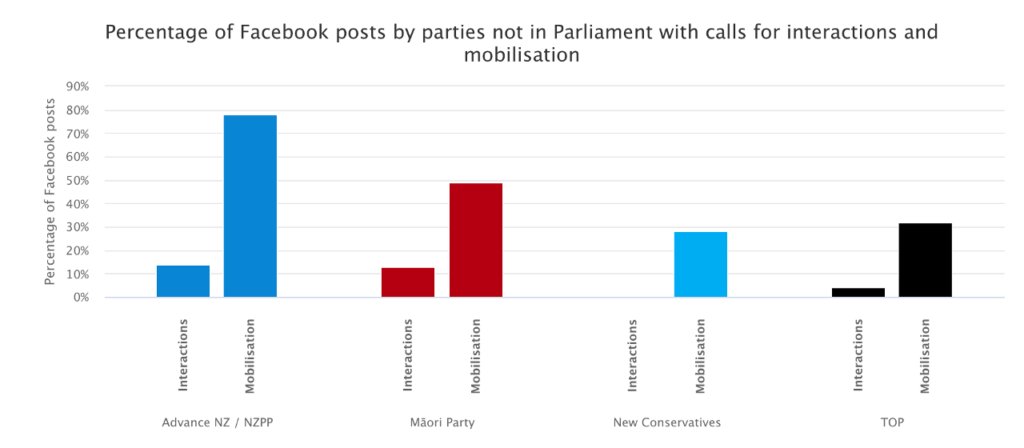

But are the Facebook campaigns of New Zealand parties mobilising us to engage in the campaign and cast our vote? Do the parties actively interact with voters in their Facebook campaigns?

“Looking at the results, New Zealand’s parties are not running a very engaging campaign so far,” says Dr Krewel. “For a long time, scholars of political communication thought social media would contribute to more direct and more real interpersonal communication between politicians and voters. But more and more studies have shown this was a false hope. Most social media communication by parties is top-down. Parties seldomly really interact with voters on Facebook and other social media. New Zealand is another example to confirm this behaviour, as only a small number of party posts call for voters to interact with the parties.

“The parties are doing better at mobilising voters, as of course they want their votes. Among the established parties, it is not hard to identify those currently working hardest to mobilise their voters: the Green Party and New Zealand First. Based on recent polls, New Zealand First fears it will not get back into Parliament. While most recent polling puts the Green Party above the 5 percent party vote threshold, the Green level of support is still too close to the threshold for comfort, and consequently the Green Party is also working hard to mobilise its supporters.”

Advance New Zealand is the only party that currently works harder to mobilise support than the Greens and New Zealand First. “But their high mobilisation score does not result from calls to vote; it originates from their attempts to get people to rally against the Government’s COVID-19 policies,” says Dr Krewel.

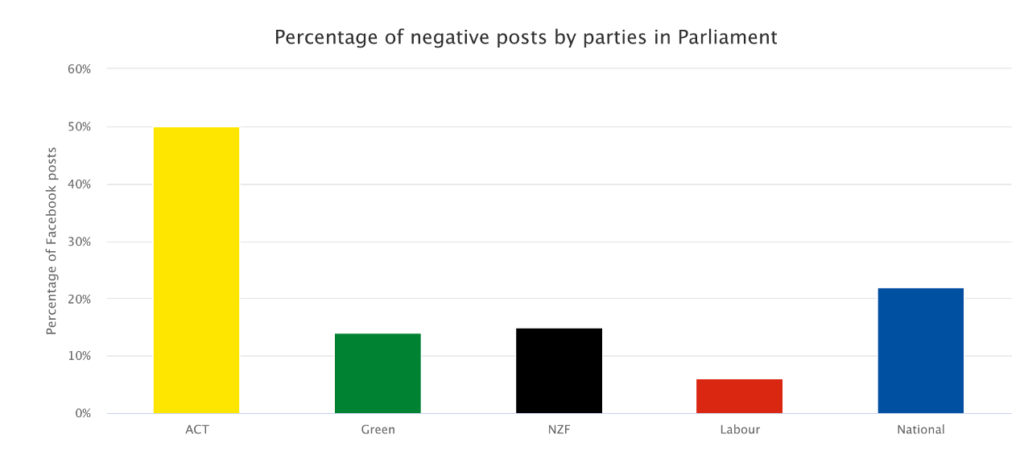

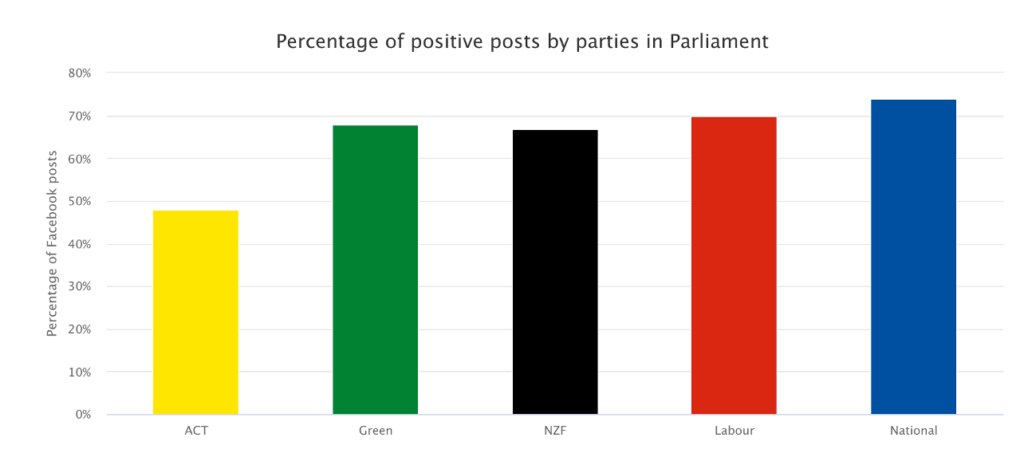

Are New Zealand’s parties also actively demobilising voters by using more negative than positive language and arguments?

“We are fortunate this is not generally the case,” says Professor Vowles.

“Posting by most of the established parties in Parliament contains less than 20 percent negative information. But the stand-out exception here is ACT. Around half their posts contain negative campaigning language. In contrast, only 6 percent of Labour’s Facebook campaigning is negative. It seems Labour leader Jacinda Ardern is keeping her pledge of being a ‘relentlessly positive’ leader. But, of course, incumbents generally tend to run more positive campaigns than challenger candidates. With the exception of ACT, all the parties elected to Parliament at the last election in 2017 are running on much more positive than negative messaging.”

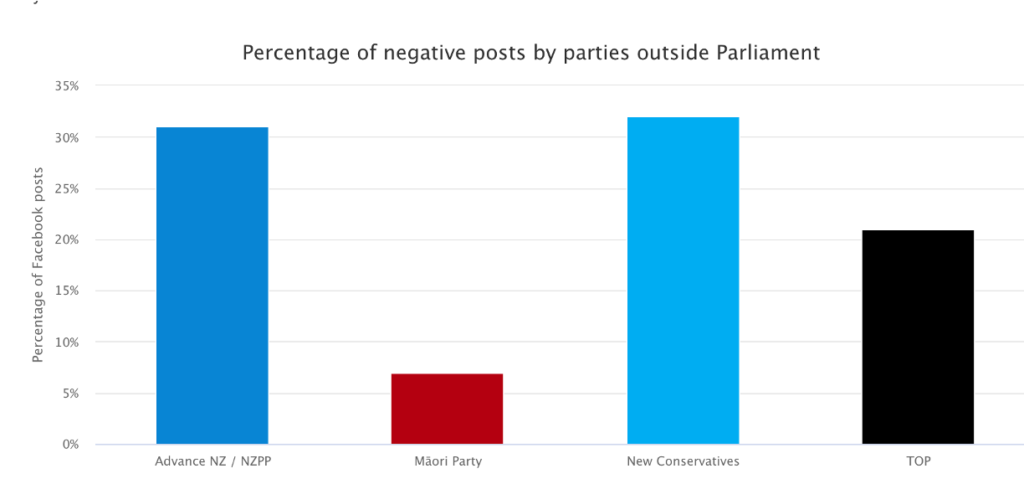

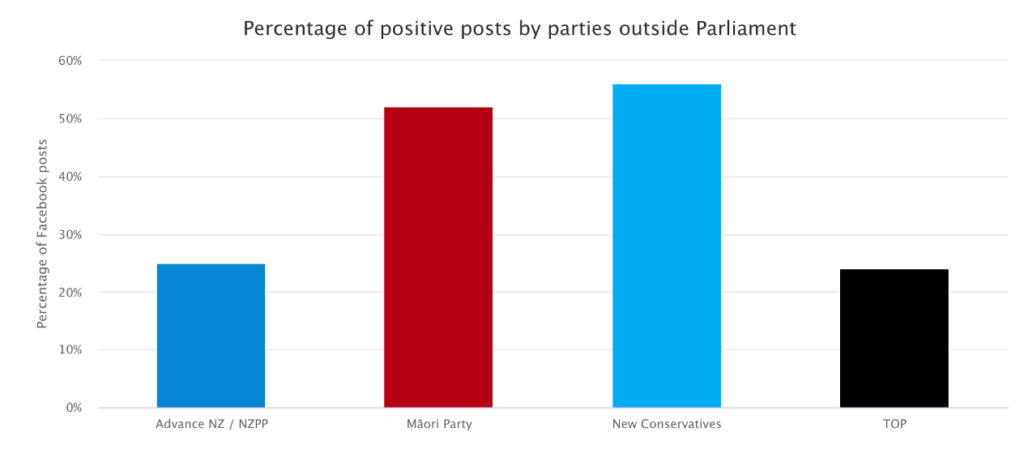

“Turning to other smaller parties, with the exception of the Māori Party they are choosing a more negative strategy. This makes sense, as having formed recently, or not having been represented in the current Parliament, they have to attract more attention,” says Dr Krewel.

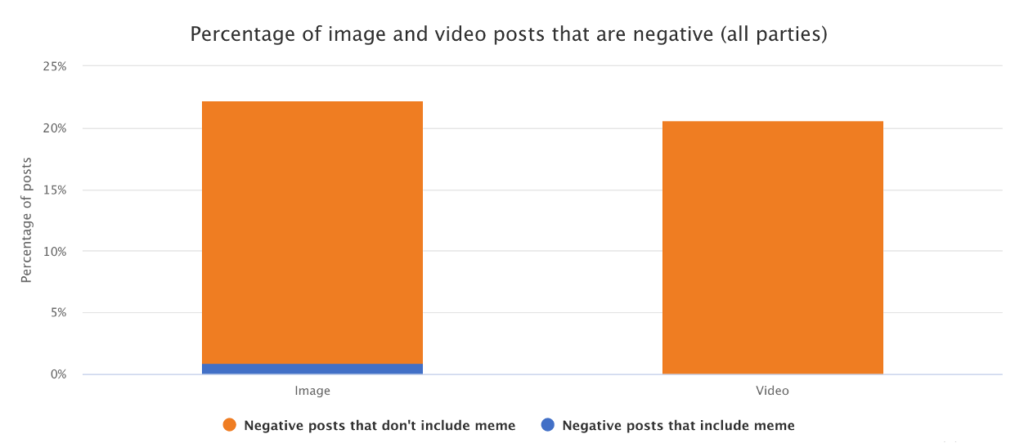

“Negative campaigning can take a variety of forms,” she says. “Many people assume political memes are responsible for a lot of the negativity they see in campaigns. Memes are pictures that have been altered to become humorous by incorporating new elements or comments into the original picture. The intent is to make fun of something or someone. Effective memes tend to spread quickly. They have become prominent in politics and campaigns all around the world.”

However, in New Zealand memes do not feature strongly as an instrument of negative campaigning. Only a small number of negative posts in the election campaign so far have included memes.

“I don’t want New Zealand to fall into the trap of the negative fake news style campaigns that have taken place overseas in recent years,” Jacinda Ardern said in January this year, long before the campaign. More than eight months later, it seems most parties have heard her and agree with her sentiments.

Over the first two weeks of the study, most political parties did not spread fake stories on Facebook. This is good news for the quality of democratic political discourse in New Zealand, says Professor Vowles.

“As we pointed out in our first post, the exception is National Leader Judith Collins, who posted a selectively edited section from the first leaders’ debate to make it appear Jacinda Ardern had made a negative comment about farmers that she did not say and denied saying.”

He observes that Judith Collins has made a few other questionable ‘off the cuff’ statements on the campaign trail, but these have not been repeated on social media.

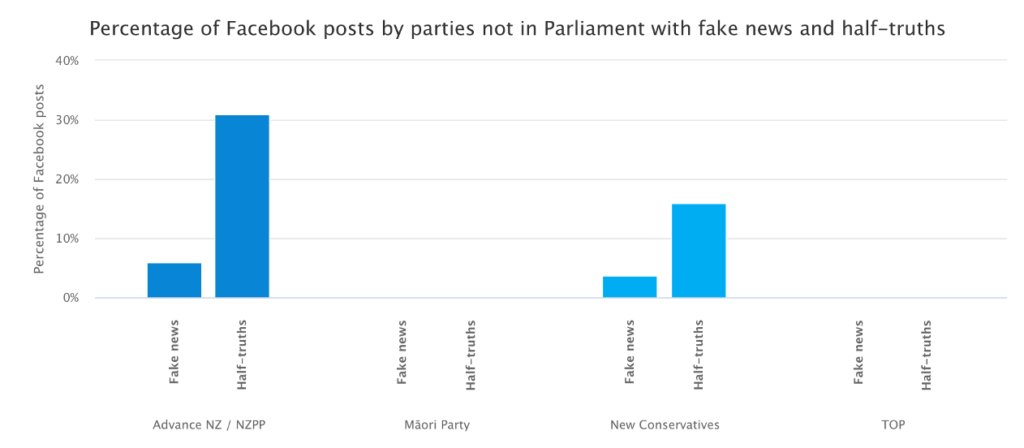

“The only parties spreading fake news on Facebook are Advance New Zealand and the New Conservative Party. This is not surprising. Advance New Zealand—which also incorporates the New Zealand Public Party—is a new party that needs a lot of media attention to have a chance of success. Negativity or conflict increases the ‘newsworthiness’ of stories.

“Already before the start of the election campaign, the New Zealand Public Party was spreading conspiracy stories, including the claim the COVID-19 pandemic was planned by the United Nations. It is disturbing most of their misinformation is about COVID-19. If widely believed, it has the potential to become life-threatening.”

Much of the misinformation propagated by the New Conservatives is about abortion, says Professor Vowles. “They are very much against abortion and tend to share content and pictures that originate from religious right-wing groups in the US.”

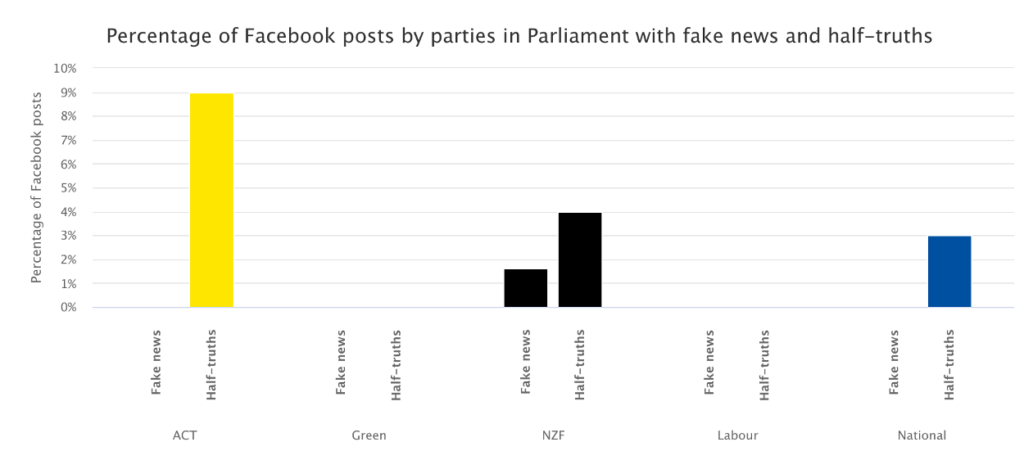

However, even if the established parties are not engaging in fake news on Facebook, their posts contain some ‘half-truths’, says Dr Krewel.

“We define these posts as containing information that is not completely made up but still contains questionable content that is not fully accurate. These are the statements that can fly under the radar of fake news. In particular, ACT stands out again, and as a party in parliament it should definitely do better. As their campaign is also the most negative, they are another case to monitor closely. This kind of campaigning behaviour can lead to increased disaffection with democratic politics.”

“New Zealanders deserve a positive election,” said Jacinda Ardern. But are they getting it? “For the most part our answer is yes,” says Professor Vowles.

According to Dr Krewel, New Zealand campaigning is not replicating the experience of the US yet, but the quality of information political parties provide New Zealanders could still be higher. “We can always do better. As our research shows, parties could interact more with voters instead of communicating with them top-downward. They should also be more careful and refrain from spreading half-truths.”

CrowdTangle, a public insights tool owned and operated by Facebook, has been used to collect the data on which this commentary is based. This sample has then been coded by five human coders on the basis of CamforS/DigiWorld’s codebook.

Radio Interview with Radio Ngati Porou about the New Zealand Social Media Study (NZSMS)

This week I was interviewed by Radio Ngati Porou about our study of the campaigns of New Zealand’s parties and their leaders in the ongoing 2020 election.

You can listen to the full interview here.

Interview with TVNZ 1 News at Six

Today I spoke with TVNZ News at Six about lowering the voting age to 16. Watch the entire interview here.

New blog post: From dirty dairying to dirty campaigning? The duel between Jacinda Ardern and Judith Collins on Facebook

Repost from Te Herenga Waka Victoria University’s Website

Over the past fortnight, Labour’s Jacinda Ardern and National’s Judith Collins have faced off in two televised leaders’ debates. But how is the ‚Stardust vs the Crusher‘ duel going on social media? Who is posting more? How are their followers reacting to their posts? Which topics do they focus on? How informative are their campaigns? And how ugly does it really get between New Zealand’s two candidates for Prime Minister on social media? Are we seeing the beginning of a ‘dirty campaign’?

In their content analysis study of social media, Professor Jack Vowles and Dr Mona Krewel from Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington’s Political Science and International Relations programme have coded and analysed 599 Facebook posts placed by political parties and their leaders for 17-24 September, and will continue to do so over the coming weeks until election day on 17 October. The parties covered are Labour, National, the Greens, New Zealand First, ACT, The Opportunities Party, the Māori Party, the New Conservatives, and Advance New Zealand.

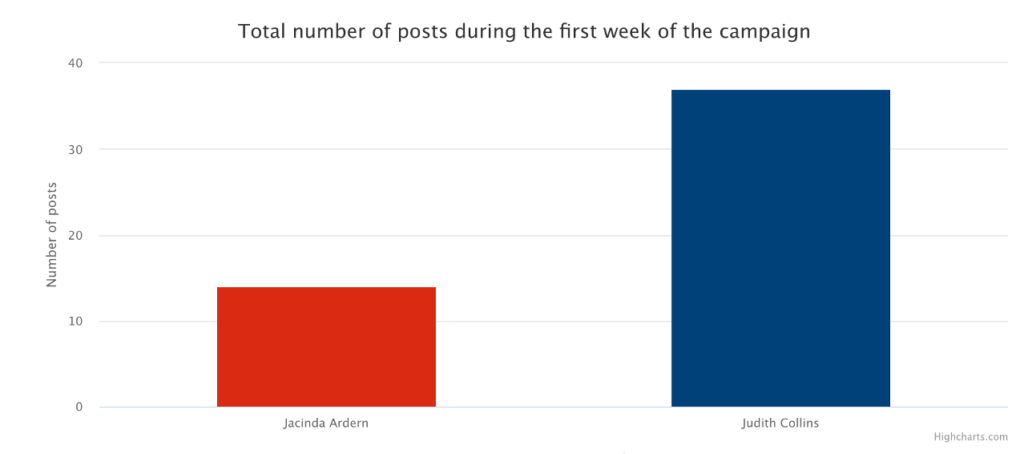

“Of those 599 Facebook posts from the first week of the four-week campaign, 51 came from Jacinda Ardern or Judith Collins. We look at these posts in our first analyses. We do stress that the number of posts from only one week of data collection of course is still very small. In the coming weeks, we will be able to get a much clearer picture of how the candidates are campaigning after we have analysed more posts and our data set has grown,“ says Professor Vowles.

Dr Krewel says: “If we just look at the sheer number of posts, we see Judith Collins has posted more than twice as much as Jacinda Ardern. This might come as surprise to some, as Jacinda Ardern is seen as New Zealand’s social media powerhouse. However, this is not a surprise for political communication scholars.

“The literature classifies all communication by parties and candidates themselves as ‘paid media’. Research has shown challenger candidates such as Judith Collins use all forms of ‘paid media’ more than incumbent candidates. They invest more in television advertisements and in social media for the simple reason they need to level the playing field, because incumbents such as Jacinda Ardern automatically get more ‘free media’ or ordinary journalistic coverage. We call this an incumbent bonus. Given this, it is natural Judith Collins posts to reduce that bonus.“

Professor Vowles adds: “There is a big difference in followers between the two leaders. Jacinda Ardern currently counts around 1.7 million followers and her Facebook page has nearly 1.4 million likes whereas Judith Collins only has 62,000K followers and 59,000 likes. Judith Collins is well advised to post more to increase her prominence and popularity.”

However, more posts do not automatically result in an advantage. So how have people reacted to the posts?

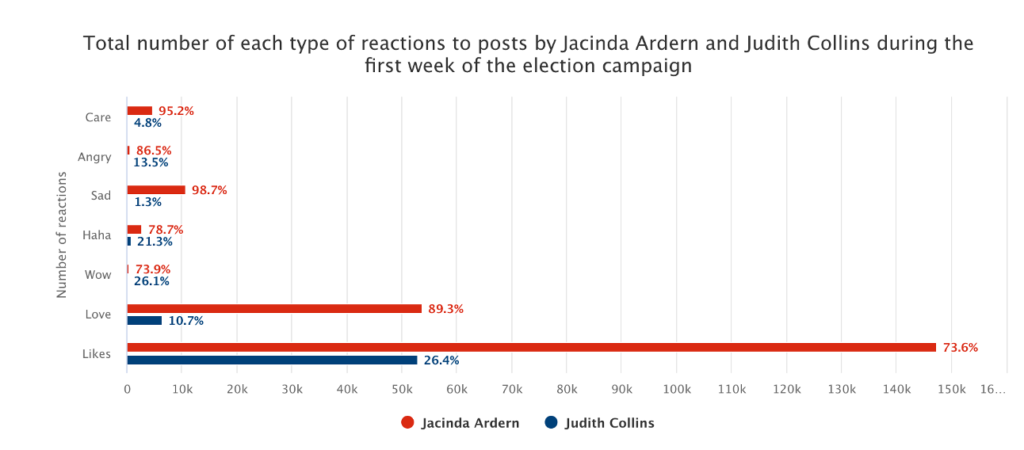

“First of all, in both cases, the answer is mostly positive. Most of the reactions both party leaders receive are likes and loves. The negative Facebook ‘angry’ emoji is used rather seldom. The reason for this is self-selection. Most of the people who follow a politician on social media do it because they like the person and want to support them and express their support publicly. Liking a politician on Facebook is a modern version of putting a sign into your garden to advertise the party and make clear where you are standing politically. The majority of the people who see most of Jacinda Ardern’s and Judith Collins’s posts are Labour and National partisans who support them and their work and express this with a positive emoji,” says Professor Vowles.

But who is doing better? “Here Jacinda Ardern clearly has an advantage. She has around three quarters of all likes, whereas Judith Collins only receives about one quarter. This picture is even more extreme when we look at the loves. However, Judith Collins also receives much fewer ‘sad’ and ‘angry’ reactions than Jacinda Ardern,” says Professor Vowles.

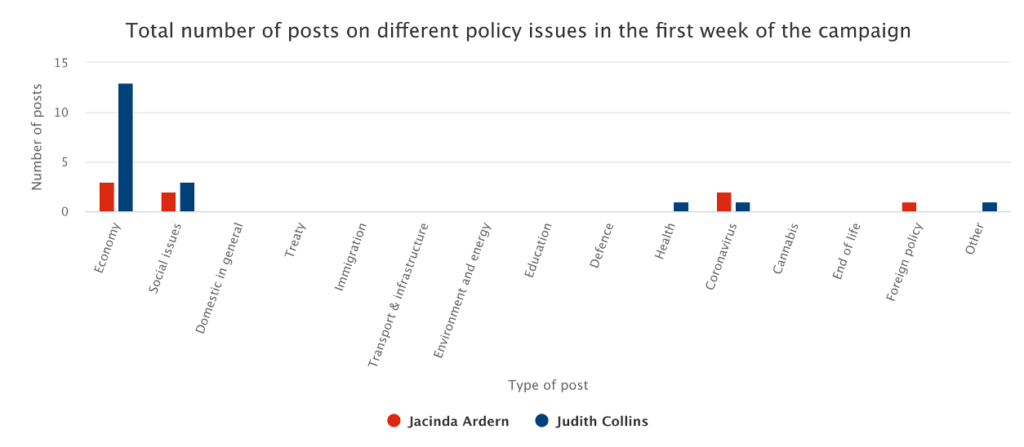

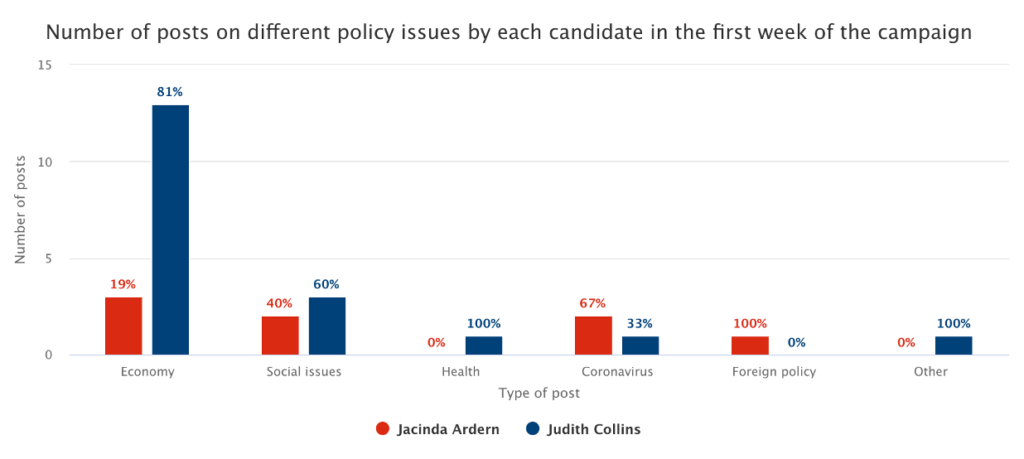

Looking at the topics on which both candidates focused in the first week of the so-called ‘hot campaign’, the graph above shows the most frequent topics in Jacinda Ardern’s and Judith Collins’s social media posts.

“The economy dominates the social media campaigns of both leaders,” says Dr Krewel. “This is not surprising, as not only in the times of COVID-19 but also in other times the economy is always the most important topic in every campaign around the world. Similarly, voters’ survey responses regularly show they believe the economy is the most important topic. To put it in the words of United States President Bill Clinton’s campaign manager James Carville: ‘It’s the economy, stupid.’”

“Besides that,” says Professor Vowles, “both candidates focus on social issues and—surely a result of the COVID-19 crisis—health in general and COVID-19 in particular.”

However, looking more closely at the most important topics in the graph below, one can note that Judith Collins focuses her campaign more on the economy than Jacinda Ardern.

“This is because voters who focus on the economy tend to believe National is more competent at governing the economy than Labour: indeed, this is true for most economy-focused voters around the world, who tend to favour conservative parties. Judith Collins is therefore emphasising a traditional strength of her party,” says Professor Vowles.

According to Dr Krewel, it is more surprising Judith Collins also focuses more strongly on social issues than Jacinda Ardern. “Competence and commitment to social issues are more characteristic of social democratic or Labour parties around the world. Jacinda Ardern might be well advised to bring that strength of her party to the forefront of her campaign.

“Nonetheless, the weaker emphasis on social policy in Jacinda Ardern’s campaign compared with Judith Collins’s can be explained. As New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern has been busy fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, her Facebook posts focus more on COVID-19 than Judith Collins’s posts as the leader of the Opposition. As the Prime Minister’s response to the pandemic has been applauded in New Zealand and around the world, it is a smart campaign strategy to focus on that topic.”

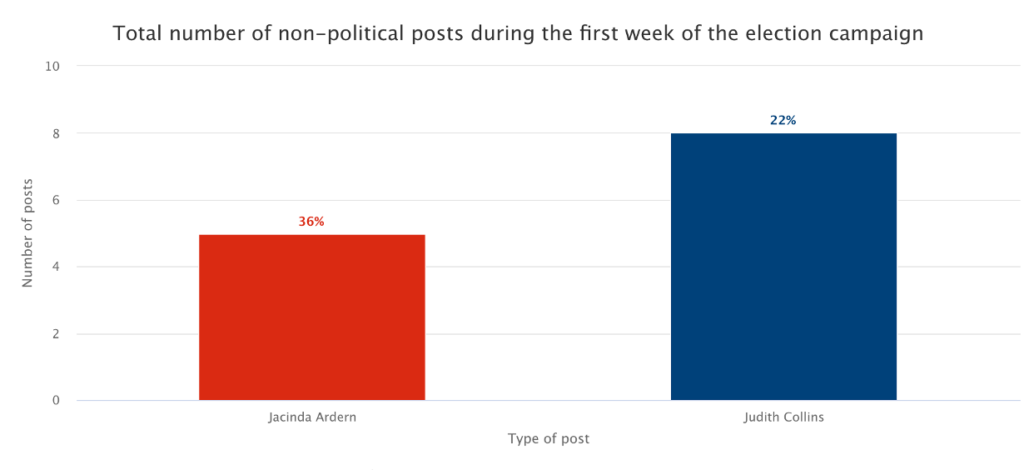

Not all topics brought to the fore in election campaigns are political.

“Social media demands a more informal style of political communication from politicians than traditional media. We very often also see politicians posting on non-political matters and giving us a glimpse of their private lives. This helps them to appear more human and more likeable,” says Dr Krewel.

Professor Vowles points out: “Thirty-six percent of Jacinda Ardern’s posts turn out to be non-political, compared with only 22 percent of Judith Collins’s posts. Compared with the first television debate, during which Judith Collins stressed her personal experiences and her own life much more than Jacinda Ardern, on social media Jacinda Ardern has made up for that omission and has spoken about non-political topics.”

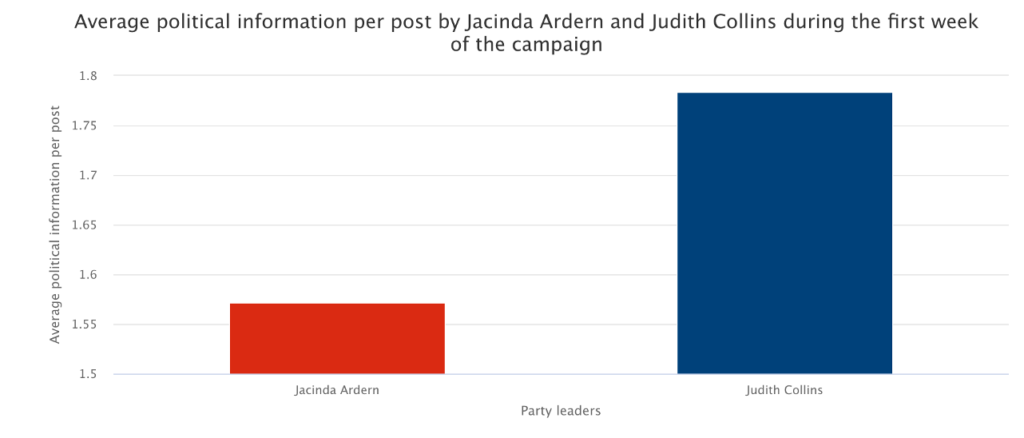

How informative are the leaders in their posts? “The normative democratic ideal of an election campaign is it should inform voters. Many justify the increasing use of social media in politics by claiming it helps voters to become more informed,” says Professor Vowles.

“On average, Judith Collins’s posts contain more political information than those of Jacinda Ardern. This makes sense, as Judith Collins still has to promote her policies, whereas Jacinda Ardern has been governing for four years and people know her record. Jacinda Ardern’s national and international popularity is very high, which means she can also campaign on her personality given her sky-high ratings. Judith Collins still has to convince people on the basis of her arguments as well as her personality.”

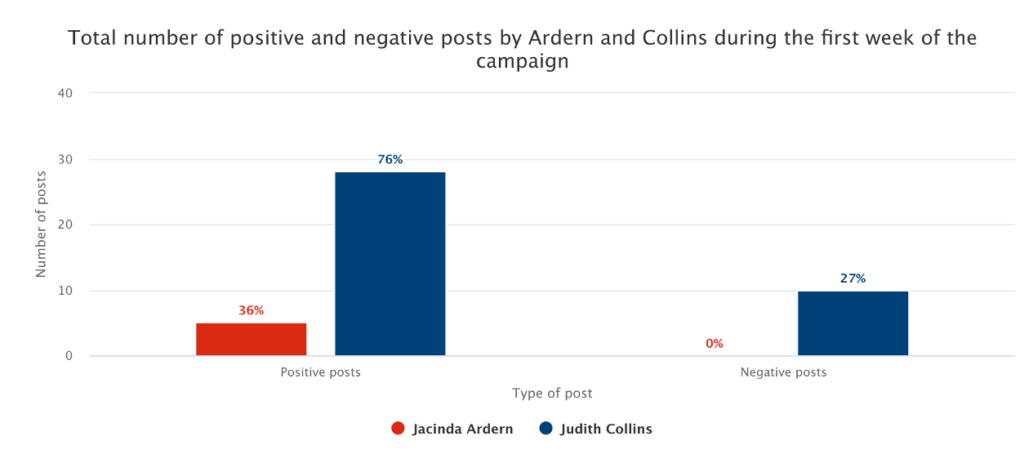

Finally, how negative were the posts made by the two leaders in the first week of the campaign?

According to Dr Krewel, Jacinda Ardern, at least on Facebook, seems to have kept her promise of avoiding negative campaigning, whereas Judith Collins has already gone negative and is living up to her reputation of being the “Crusher”.

“From a strategic standpoint, it makes sense for Jacinda Ardern to stay away from any dirty campaign techniques and not to attack Judith Collins personally,” says Dr Krewel. “Negative campaigning can backfire on the attacker. Currently, Jacinda Ardern is very popular and has a reputation for having a clean record. The chances she could damage her image by going negative are higher than any possible gains.

“Challenger candidates like Judith Collins are more dependent on journalistic media attention. Journalists and media editors are the gatekeepers who pick and select stories, making decisions at least partly based on news values. One important news value is negativity.”

To Professor Vowles, the targets of Judith Collins’s attacks also make a lot of sense: “Her negative posts mostly attack either Labour or the Government as a whole and—but to a lesser extent—the Green Party. Of course, Judith Collins must mainly focus on Labour, as the Labour Party is National’s biggest competitor. She also reinforces her followers’ beliefs that the Government has done a bad job and Jacinda Ardern and Labour need to be voted out of office.”

The most extreme version of negative campaigning is ‘fake news’—making up or misinterpreting evidence to make a claim that can be refuted by evidence.

“One clear example has appeared in our data, made by several National MPs but also by Judith Collins herself,” says Professor Vowles. “In this Facebook post, a selectively edited section from the first leaders’ debate is used to make it appear that Jacinda Ardern described a defence of dairy farming in general as ‘the view of a world that has past’. But in full context, Jacinda Ardern’s comment was about ‘dirty dairying’, the defence and practice of which she ascribed to a minority of farmers.

“Jacinda Ardern went on to applaud farmers meeting the challenge of sustainability as ‘climate change warriors’. Indeed, in the debate itself she directly denied Judith Collins’s assertion that she had said farming was a ‘time of the past’. ‘No, it’s not,’ she replied. In this, we see our first clear example of ‘dirty campaigning’ by one of the two party leaders here.” (For the full exchange, see Newshub.)

Looking at these first results, Associate Professor Kate McMillan, Head of the Political Science and International Relations programme at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington, says: “This study of social media during Election 2020 will shine light on crucial information that is otherwise hidden in individuals’ private Facebook feeds: how the different parties and candidates are communicating with voters during the election campaign. This is incredibly important at a time we see growing awareness of and profound concern about Facebook’s role in elections around the world. The more visibility given to the social media strategies of all parties this election the better.”

Note: CrowdTangle, a public insights tool owned and operated by Facebook, has been used to collect the data on which this commentary is based. This sample has then been coded by five human coders on the basis of the CamforS/DigiWorld’s codebook.

Podcast: New Zealand Election 2020: Key social media trends w/ Jennifer Windsor, Jack Vowles & me

If you always wanted to know how a study on the Facebook campaigns of the parties and the top candidates in an ongoing election campaign is conducted, I recommend Victoria University’s newest podcast with Pro Vice Chancellor Humanities and Education Jennifer Windsor, my colleague Jack Vowles and me about our current social media study. Now available on Soundcloud , Spotify and iTunes (free for republication). Publication of the results in weekly blog posts begins this Friday and I’m very excited as the first data came in today. I hear we will compare Jacinda vs. Judith in our first post: how did our two female top candidates start off into the hot campaign phase of the last four weeks? Who is doing better on social media? Stay tuned, link to be posted here this Friday!